TWO PLUS TWO MAKES FOUR

THE AUXILIARY WAREHOUSE

16TH FEBRUARY - 24TH MARCH 2023

CURATED BY LIZZ BRADY AND BROKEN GREY WIRES

Helvetica Light is an easy-to-read font, with tall and narrow letters, that works well on almost every site.

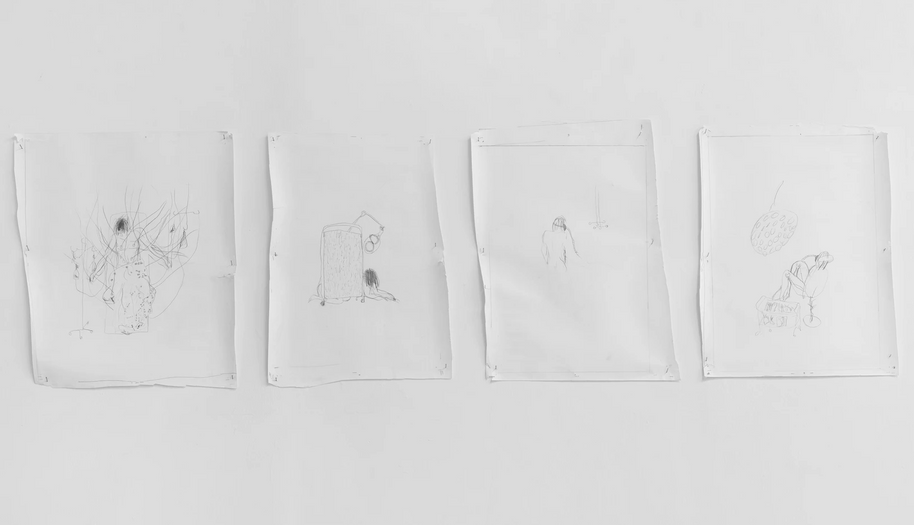

Photos by Rachel Deakin

Exhibiting Artists: Vito Acconci / Gina Birch / Lizz Brady / Connor Clements / Thomson + Craighead

Martin Creed / Tim Etchells / Luke Fowler / Jochen Gerz / Kirsty Harris / Daniel Johnston / Tsoku Maela

Sade Mica / Pipilotti Rist / Kier Cooke Sandvik / Gillian Wearing / Joseph Whitmore / Oliver Ventress / Bill Viola

Two Plus Two Makes Four curated by Lizz Brady (Broken Grey Wires) creates a space for audiences to catch their breath and explore the mental health crisis through an ambitious and challenging project.

Featuring work from leading artists, including Bill Viola, Pipilotti Rist, Gillian Wearing, Martin Creed, and the late American, DIY artist Daniel Johnston. The show features work on paper, neon, photography, interactive installation, and video.

The work exhibited in Two Plus Two Makes Four is rooted in the lived experience of mental illness. It spans the sombre, the joyful/funny, and the raw and explores the politics of mental illness.

The project encourages interaction and conversation with a Mad Manual Toolkit to use in the gallery, and The Comfort Zone, a dedicated chill-out space where visitors are invited to relax and reflect on the show.

Broken Grey Wires breaks down societal stigmas and promotes art as a facilitator for recovery, however recovery manifests for the individual.

Through our personal understanding of mental ill health, Broken Grey Wires creates spaces for people to experience madness in a radical and ambitious, yet safe environment.

DAZED AND CONFUSED ARTICLE HERE

READ THE DOUBLE NEGATIVE ESSAY ABOUT MY WORK BY MIKE PINNINGTON BELOW AND HERE

Mike Pinnington of Double Negative wrote an essay on my work:

http://www.thedoublenegative.co.uk/2023/02/probably-just-a-wrong-number-on-kirsty-harris-cold-call/

In an essay excerpted from the catalogue for Two Plus Two Makes Four – an exhibition ‘rooted in the lived experience of mental illness’ – Mike Pinnington responds to anxieties found in the work of artist Kirsty Harris…

Probably just a wrong number...

The phone rings just as you step under the shower head and begin lathering shampoo into your hair. Typical, you think. Whatever it is, whoever it is, it’ll have to wait. But as the chirpy, irritating trill continues unabated, frustration subsides, and is replaced by something else. You feel it in the pit of your stomach, this something else. It takes over. Slowly at first, but it grows. You run through the possibilities. Who’s calling at this hour? You see sense, dismiss it. If it’s important, they’ll call back. And, anyway, it’s probably just a wrong number, you reason to yourself. But… Still, the phone rings. It sounds more insistent now. Menacing. As if to match it, your heart quickens, concern creeping increasingly in. Finally, manically, furiously half-rinsing the shampoo out of your hair, you reach for a towel. Heartbeat outpacing even the ringtone, now, anxiety is beginning to get the better of you. You admonish yourself: take a breath, damnit, still pretending it’s probably, almost definitely, nothing. Stepping out of the shower into the hallway, nearly cracking your head against the wall as you barely pre-empt a slip, you grab the phone, juggling the receiver with a wet, soapy hand. Yes? you bark, who’s there, what is it?

There is no ‘live’ voice as such on the other end of the line, though; instead, there’s a pre-recorded official-sounding message of some kind. And even though you’ve known all along that this message would reach your ears one day, it isn’t really filtering through. Not really. What? Can you repeat that please? you ask robotically, knowing nobody is listening to the question. Shortly, the blinding flash of light provides all the information you need. Your eyes tightly closed, you can still see the afterimage, etched onto your retinas. It is followed not long after by a chilling, rumbling whoosh to end all whooshes as the windows are blown in and dust and debris flies everywhere.

*

Up until Putin’s invasion of Ukraine terrifyingly put the option back on the table, it seemed beyond crazy to think that, not so very long ago, the idea of nuclear Armageddon was a very real possibility, just something people lived with. An ever-present background concern, although it nagged occasionally, the post baby boomer generation growing up under this particular (mushroom) cloud had mostly managed to keep pushing the prospect of this ever happening to the periphery of their collective 1980s consciousness. In the new world order forged by President Reagan, aided and abetted by Prime Minister Thatcher, a cold war that – from today’s vantage point – began a lifetime ago still simmered, threatening to get very hot indeed well into the decade. In hindsight, I’m thankful we couldn’t readily take to social media back then, to fan the flames of already frayed nerves.

Status Update: What’s on your mind? Mutually assured destruction means no destruction, right? Right?

Said nerves were, more often than not, put to one side, absorbed by an affected (often enough to feel real), sometimes effective, blasé armour; one fashioned of apathy and wryly observed resignation at the inevitability of the fate we secretly, deep down, feared awaited us. If we were lucky, though, we’d get to speak to our loved ones when the time came; not via Zoom, or FaceTime, but in person, or on the other end of the phone – analogue, of course.

*

When I first came across Douglas Coupland’s debut novel Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, first published in 1991, it spoke to me as surely as if its author was writing directly into my mind’s eye. The book’s cast of disenfranchised twentysomethings – suspicious of and jaded by the culture into which they have been birthed – have dropped out of the rat-race to form new, less complicated (certainly less than idealised) existences. In these new lives, they occupy low-paid, low-responsibility McJobs, waiting out the future, or lack thereof. Now iconic, Generation X had an immediate, deeply felt impact on all – specifically those born between 1965 and 85 – for whom it was written. It articulated and defined all too well the characteristics and preoccupations of an entire generation. These include listlessness and ennui, resulting in an unhappy concoction of mostly feigned nihilism with sporadic states of high alert. In doing so, it couldn’t help but capture and become part of the zeitgeist.

Alongside its central narrative, Coupland littered his era-defining debut with definitions, factoids, text artworks and observations – what amount today, to a lexicon for, and means to grapple with, the times.

Mental Ground Zero: The location where one visualizes oneself during the dropping of the atomic bomb; frequently a shopping mall.

*

Many of the concerns, contradictions and anxieties Coupland addressed in his book are found in the work of artist Kirsty Harris; in-particular the threat – both real and implied, physical and psychological – posed by the ‘bomb’. A Gen Xer herself (born in 1978, Harris is on the younger end of the scale), she has stated that her work addresses “The decisive moment, a meditation on a split second. That split second iconically representing our race to self destruction. The beauty and awe of the landscape, the dust, the glow, the force of the explosion. The myths surrounding characters in this masterplan to kill ourselves off. The fight for survival. We’ve shown ourselves THE END.”

Included in the exhibition Two Plus Two Makes Four, the 1950s rotary-style wall-mounted telephone looks innocuous; kitsch, even (the kind of kitsch we Gen Xers, sometimes unfathomably, love to love and disparage in equal measure). But at the first of its intermittent rings, your anxiety spikes. Is it a herald of THE END? Or, simply: IT IS THE END. You steel yourself. Instinctively take a breath. Finally, warily, you pick up the receiver. There is no voice as such on the other end of the line; neither, thankfully, is there a pre-recorded official message of any kind. Instead, a composition plays, beginning (I think) with the picking of double bass strings. The arrangement continues, and the double-bass is joined by piano, drums, saxophone, guitar, harmonica, shaker and triangle. Together, they make for a compelling modernist-sounding piece of music. Its effect is eerie, sparse, occasionally jarring. If you were to sit in the audience as an orchestra played this piece, you’d likely find it powerful and captivating, although you’d perhaps be uncertain as to why.

This is Cold Call (How I Learned to Stop Worrying (1945-2019), an interactive installation which, as with all of Harris’ work, is based on the imagery and data collected on the atom bomb. Here, the notes played on the various instruments represent – in fact, are – musical translations of nuclear detonations made by different participating countries since 1945. (The first atomic bomb, named “Little Boy”, was dropped on Hiroshima from the Enola Gay, a B-29 bomber, at 8:15 AM on August 6, 1945. Each instrument represents a country – the double bass is the USA; the piano the Soviet Union; the drums France, and so on and so forth. In total, its five or so minutes encapsulates more than 2,000 explosions. Each note depicts a single bomb, there are lulls and short silences before the quiet is filled by the crash of keys or the warning of the sax. The calm before the coming, maybe decisive, storm.

*

“Every generation thinks it’s the end of the line” said Douglas Coupland in an interview on the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of Generation X. He’s not wrong. But in the beautifully, magnificently frightening work of Kirsty Harris we see demonstrated very eloquently why – and this is no prideful boast – we genuinely, terrifyingly thought ours, ultimately, was the one with a claim to Death, the destroyer of worlds.

Mike Pinnington